Art Basel Viewing Room

Head-Image

Ah Pitzlaw, 2011

Wood, polystyrene, cement, and acrylic

Overall: 65 3/4 x 39 1/2 x 33 1/4 inches (167 x 100.3 x 84.5 cm)

(RH.998)

Originally exhibited as part of Rachel Harrison’s mixed media installation Incidents of Travel in Yucatan (2011), Ah Pitzlaw is modeled after the stone goal hoops used in the ritualistic game of life and death that took place on Mesoamerican ballcourts. The hoop crowns a sculptural form painted in vibrant stripes of pink, red, yellow, green, and turquoise, dusted with metallic highlights, the whole sited on a pedestal turned on its side. With various marks of age including scratches, tape, and holes once used to hide cords for video equipment, the pedestal bears traces of its previous life in museum display and storage that act in contrast to the shimmering finish on the form above. Titled after a Mayan phrase meaning “he the ballplayer,” often used by kings as a royal title, Ah Pitzlaw examines notions of artifact, cultural appropriation, global systems of exchange, and institutional modes of display.

Jacqueline Humphries

YHY///, 2020

Oil on linen

100 x 111 inches (254 x 281.9 cm)

(JH.6123)

Jacqueline Humphries’ painting practice is founded upon a poignant elaboration on the history of painting and its adaptation to new technologies, and a self-reflective evaluation of contemporary digital and screen cultures. In 2014, Humphries began her well-known ASCII paintings, in which earlier works are recast in the alphanumeric parameters of ASCII, a character-based image encoding system that dates back to the 1960s. Using this ASCII-generated code, Humphries translates her paintings into stenciled grids of typographical marks, through which she then pushes paint onto her canvases. In YHY///, muted maroon ASCII characters on the left side of the composition read as painterly gesture from afar, echoing the broad strokes and drips of pink paint on the right. Juxtaposing these two modes of mark-making—traditional brushstroke and stencil-mediated application—Humphries presents an intriguing and nuanced investigation of gesture and perception. In this work, as in much of her practice, Humphries explodes the contemporary viewing experience, demanding her viewer’s physical presence, movement, and prolonged attention.

Andy Robert

Three Fold, 2020

Oil on linen, hinges, door knob

Overall: 145 x 96 x 10 inches (368.3 x 243.8 x 25.4 cm)

(ANR.012)

Andy Robert constructs narrative in his work through a distinct intertwining of individual and shared histories that cross boundaries of time and culture. By following dynamic thought processes and threads of associations, he locates interconnected relationships among disparate themes and subjects, addressing social concerns through a transhistorical lens. In this work, created during a time of erupting crisis, stirring, muted black hues at the base of the painting ignite into whites and blues with a quick, light energy. The calligraphic and frenzied lines and smudges of paint project an abstract landscape with a setting sun, marked by the brass doorknob affixed to the canvas. Vertically stacking three panels, the work perverts a triptych by turning it on its side, yet preserves a link to its religious traditions through the hinges that precariously secure it. The title Three Fold “speaks to something explosive,” according to Robert. Teetering and top-heavy, balancing fragility and strength, unpredictability looms in the seemingly imminent collapse of the panels, as the unknowable builds behind the vision of a door. In this bold yet vulnerable composition, Robert envisions the moment of power in flux that precedes explosion.

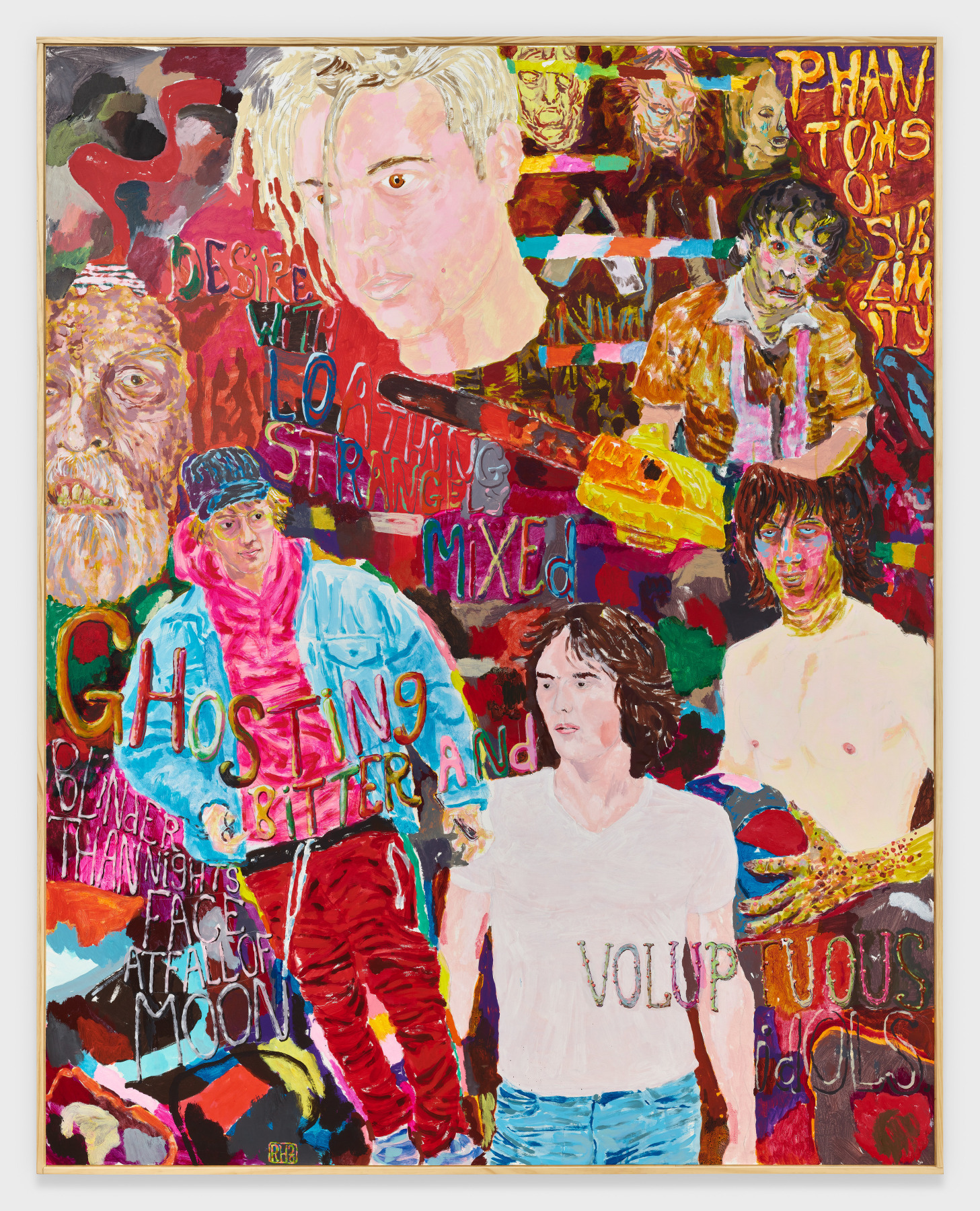

Richard Hawkins

With Loathing Strangely Mixed, 2020

Acrylic on panel in artist frame

88 1/4 x 70 1/4 inches (224 x 178.5 cm)

(RHw.155)

Richard Hawkins’s multimedia practice often reads simultaneously as vividly personal and promiscuously referential. Working in collage, painting, and sculpture, several of Hawkins’s series emerge from a process of studying, internalizing, and regenerating the ideas of historical artists and thinkers, inflected by the specificity of Hawkins’s own visual lexicon and biography. In this work, layers of sardonic texts swirl between figures of teenage heartthrobs and decaying monsters, as though eternally trapped together. These figures approximate a contemporary form of idol worship, emanating from seduction and gore.

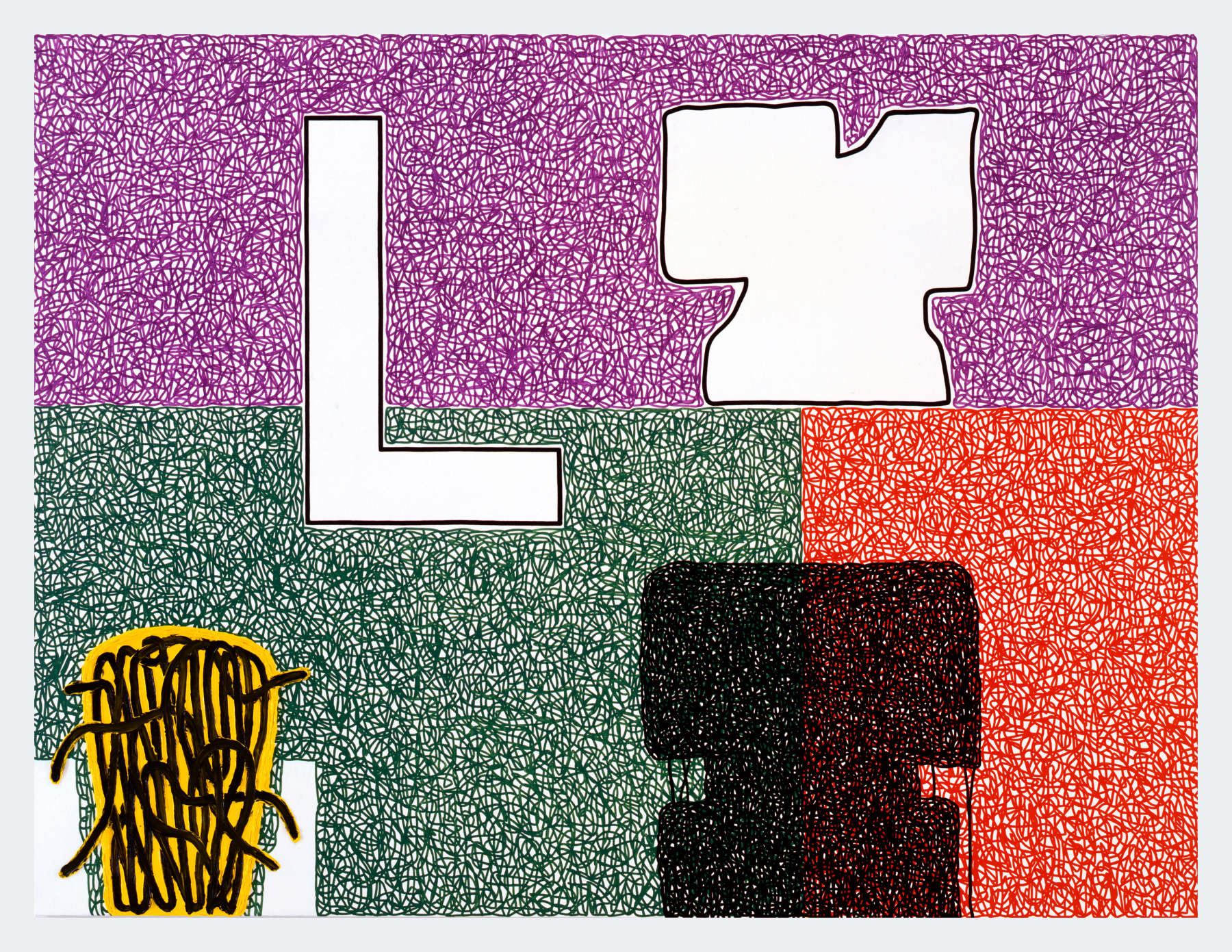

Jonathan Lasker

Drawing Blanks, 2003

Oil on linen

72 x 96 inches (182.9 x 243.8 cm)

(JLa.008)

An innovative, historical painter of the 1980s and 1990s, Jonathan Lasker has developed a distinctly singular visual language through his fluid and elusive investigation of the relationship between painting and metaphor, defining new terrain within the material concerns of the medium. His sprawling painting, Drawing Blanks, is exemplary of his painterly lexicon, through which he explores critical philosophical and theoretical discourses on semiotics. Lasker's marks function both as figure and symbol, willful yet enigmatic. Subtleties in position and layering complicate their correspondence, engaging compositional hierarchies to destabilize figure / ground relationships. Lasker's automatically-generated line refuses to fade into the recesses, while other elements both interrupt and overlap. Color, for Lasker, further complicates interpretation; the yellow, green, violet, red, and black define entities to no definitive end. Neither figure nor symbol, the white spaces are "blanks," as the title asserts, simultaneously signaling a mental lapse, an idea lost to the subconscious, and the gestural drive of the artist’s hand.

Walter Price

I still worry about the people of Flint, 2019

Acrylic on wood

16 x 20 inches (40.6 x 50.8 cm)

(WPR.581)

Walter Price’s vividly colored paintings tread the line between figuration and abstraction, providing snapshots of specificity that unground his viewer and place them in a narrative already in progress, with no definitive beginning or ending. Partially-realized figures and objects taken from his distinct visual vocabulary emerge from bustling negative space and bisecting planes of color. In this work, Price’s signature sofa and a single gray line define this interior space, populated by a repeating profile in silhouette that becomes ghostly as it fades. Space and place are complicated by a goldfish in its teal-hued plane, simultaneously present and disconnected. A sweep of blue emerging from, or materializing into, a sofa compliments the earth tones of the background, creating an in-between space connecting the fish’s world and our own. The title, I still worry about the people of Flint, contextualizes the work as a response to the Flint water crisis of 2014, which resonates within a larger meditation on society’s connection to the natural world.

Monika Baer

Untitled, 2020

Acrylic and watercolor on paper and wood, saw blade, screws

11 3/4 x 15 3/4 x 1 3/4 inches (30 x 40 x 4.3 cm)

(MB.040)

Since graduating from the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in the late 1980s, Monika Baer has maintained a singular practice in dialogue with the history of painting, orchestrating confrontations between disparate visual traditions on her canvases. Seen here, appendages to the surface and atmospheric fields of paint constitute the complex spatial logic of Baer’s compositions. The artist follows the modernist fixation with the quotidian, but also tethers her works to traditional representation. The saw blades act as a visual anchor, receding and advancing, dissolving and materializing again—flirting with the notion of a stable pictorial system.

Tony Cokes’s multimedia practice synthesizes our overloaded contemporary moment, identifying and fusing various textual and musical citations to produce clear-eyed commentary on capitalism, our spectacle-driven society, and the injustices faced by Black subjects. Cokes’s killer.mike.karaoke sources its title and soundtrack from the Atlanta-born hip-hop artist and activist Killer Mike. The songs “That’s Life 2” and “Ric Flair” (both 2011) play as their lyrics slide across the screen in karaoke fashion. Killer Mike is known for using his musical platform to connect communities and forward political dialogues, meanwhile Cokes’s artistic practice similarly encourages interdisciplinary cross-pollination and collective reckoning.

Josef Strau

Untitled, 2017

Tin plate, tin wire, acrylic on canvas

14 1/2 x 11 inches (36.8 x 27.9 cm)

(JS.028)

Inspired by a trip to Mexico and an interest in Byzantine iconography, Strau made the paintings below from tin and soldering wire. Within deliberate erosions and incisions on the tin surfaces, Strau’s palette of blues, greens, and oranges is reminiscent of one of his childhood heroes, the Vienna-born post-Secessionist painter Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928 – 2000). Strau often pairs these tin-and-wire works with printed texts: automatic writing, infused with Strau’s memories and autobiography, organized visually into concrete forms. In the exhibition space—where visual art and the written word overlap, physically and conceptually—Strau produces a narrative environment for the interplay of theory, fiction, and personal history.

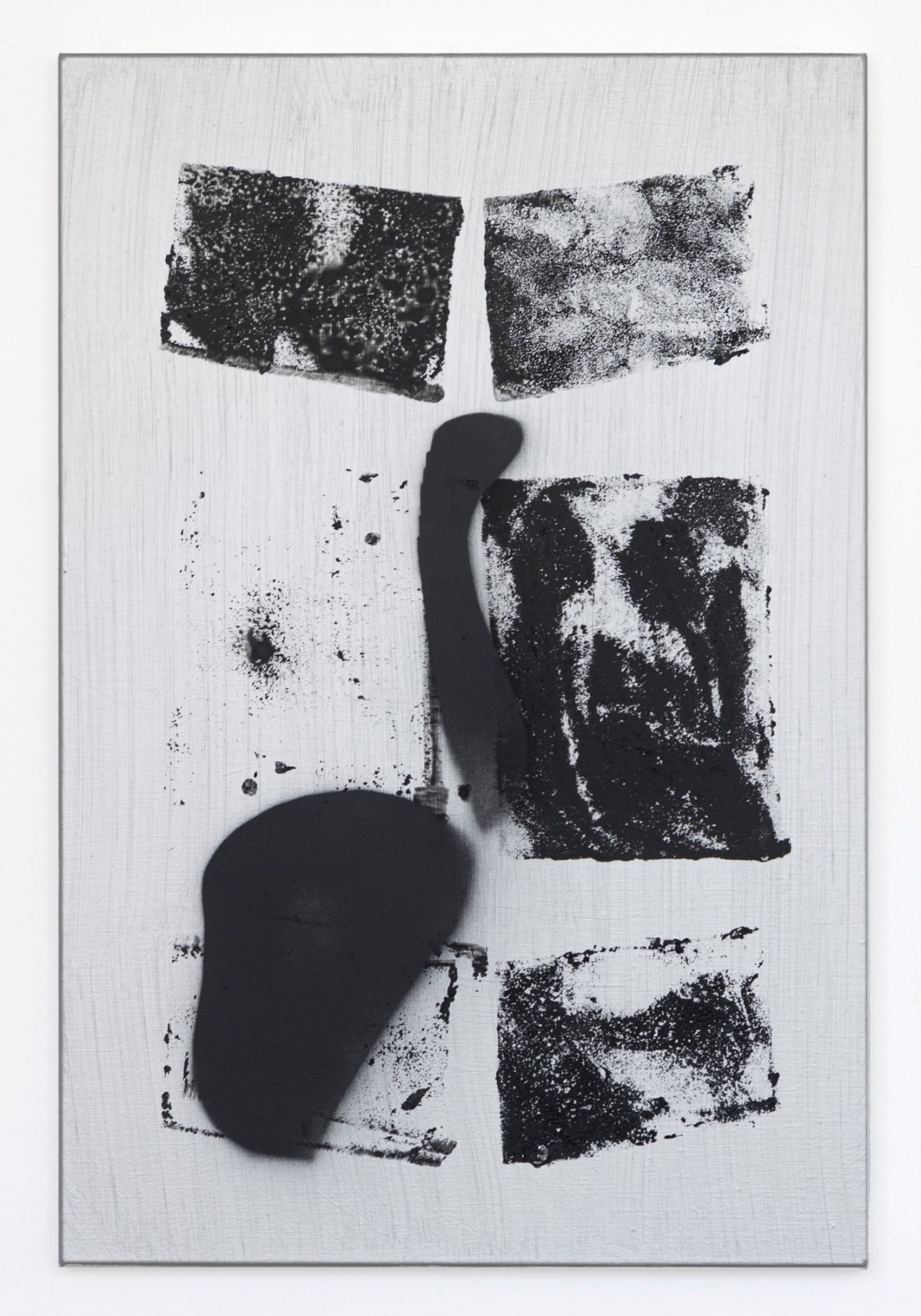

Michael Krebber

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge (1950 - 2020), 2020

Acrylic and spray paint on canvas

30 x 20 inches (76.2 x 50.8 cm)

(MK.6120)

Since the 1980s, Michael Krebber’s distinct practice has consistently offered commentary on painting and the exhibition of art. His paintings establish and obliterate their own constitutive elements, putting forth clever narratives that perennially unfold. His new work, entitled Genesis Breyer P-Orridge (1950 – 2020), uses spray paint clouds and sponge impressions to blur the painterly and textual structures that typically establish visual grammar in abstract compositions. Despite this ambiguity, the work’s title reveals its subject matter. Krebber dedicated this work to the interdisciplinary English artist Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, whose Berlin concert the painter attended in 1980. In this contemplative painting, light bounces off the metallic canvas, resurfacing fore- and background. Contradiction pulls Krebber's commemorative artwork in two directions: while it functions independently, harnessing painterly essence in and of itself, the work does not offer completeness or resolution because of its contingency upon a highly-coded system.

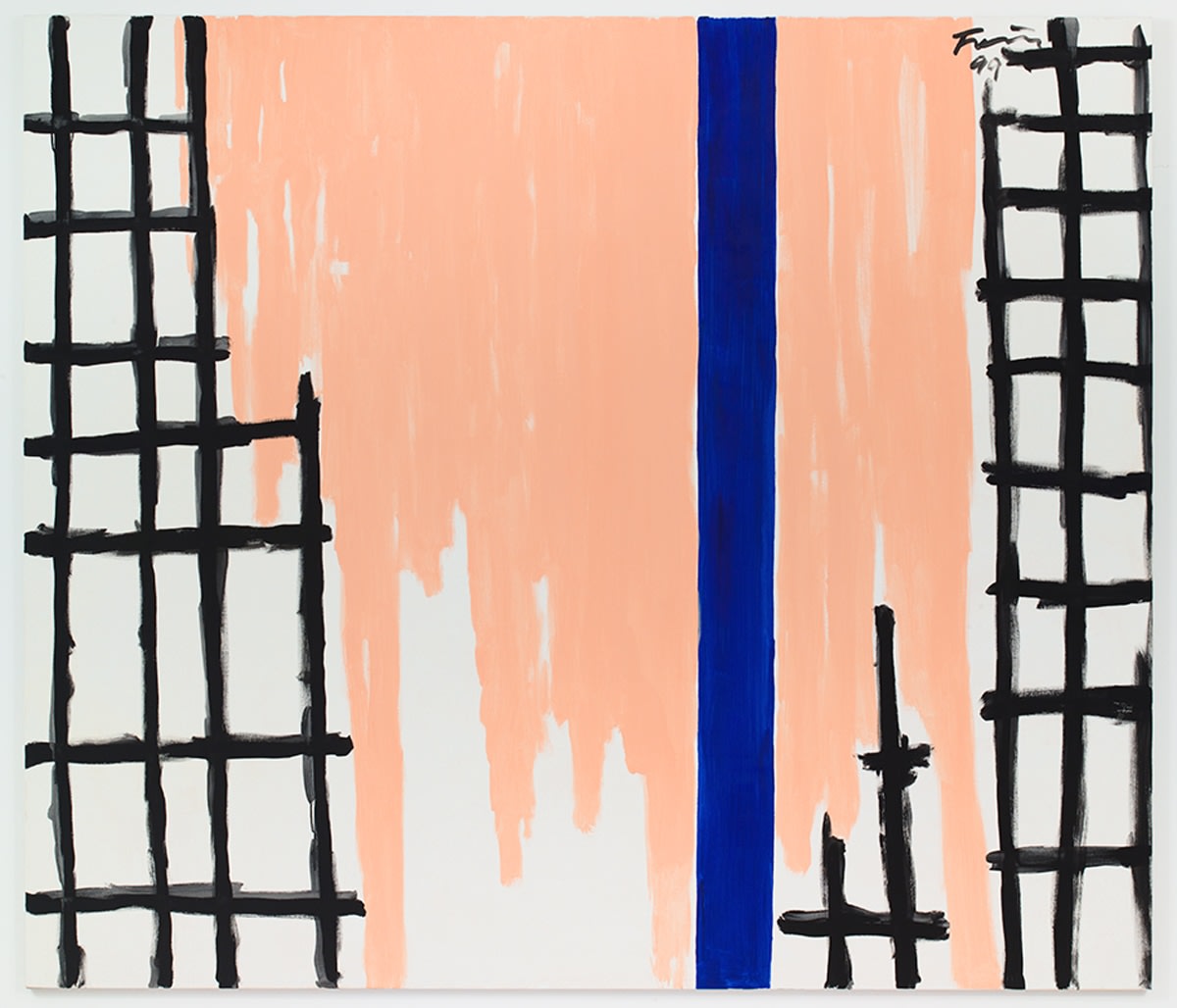

Günther Förg

Untitled, 1999

Acrylic on canvas

74 7/8 x 86 5/8 inches (190 x 220 cm)

(GF.490)

A well-known figure in the 1980s, Günther Förg (1952–2013) is a key member of an influential generation of German artists including Martin Kippenberger, Albert Oehlen, and Georg Herold. His distinct investigations into the Bauhaus and Modernism take painterly issues into the realms of architecture, sculpture, and photography to reflect on both individual experience and historical memory.

Förg produced this work in 1999, investigating his own relationship to Modernism by reinterpreting the grid structure. Evidenced by the work’s open composition, Förg considers the window’s role in painting, historically serving perspective and trompe-l’oeil. Bringing the work to the 20th century, its blue bar and contrast-heavy palette conjure Barnett Newman and Clyfford Still. While much of Förg’s oeuvre calls upon familiar Modernist techniques, his manner of doing so is rough in its calculations—reverent yet subversive, reducing the act of painting to its most elemental gesture, monumentalized on a human scale.

Giangiacomo Rossetti

Fantasia n.0 - Premonizione, 2020

Oil on wood panel

9 7/8 x 13 3/4 inches (25 x 35 cm)

(GRos.004)

Giangiacomo Rossetti’s work spans the past and present of figurative painting—resurfacing schemes and techniques from Classical art and its myriad revivals, making them the artist's own. Rossetti produced Fantasia n.0 - Premonizione (2020) after seeing Leonardo da Vinci’s Ginevra de' Benci (c. 1474/78) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Sharing a preciousness in scale, the two portraits set forth the intellect and emotion of their unaccessorized sitters. Rossetti’s time-consuming practice carefully balances the contemporary moment with art historical legacy, posturing characters from his personal life (and himself, frequently) in canonically-provocative compositions, opening a discourse on idolatry and subjectivity in the theater of contemporary painting.

Aria Dean

Mise en abyme 1.0, 2020

Blackened steel with stainless steel standoffs

43 x 36 1/4 x 2 inches (109.2 x 92.1 x 5.1 cm)

(AD.003)

Aria Dean's work frequently questions the representational paradigms that shape political and artistic subjectivities. Mise en abyme 1.0 consists of a rudimentary digital sketch of a frame within a lopsided picture plane that has been rendered sculpturally in black-oxidized steel. Appearing as a single, uniformly gray object, it in fact comprises two panels welded together, collapsing the pictorial plane and the frame into a single object with no represented subject in its bounds. The work suggests a form of non-painting, an inert object that cannot be entered into and from which nothing can be extrapolated.

Gedi Sibony

Inflection of Complexer, 2020

Salvaged plywood panel, paint

96 x 48 x 1/2 inches (243.8 x 121.9 cm)

(GS.738)

Since the 1990s, Gedi Sibony has excavated the marginal byproducts of commerce, transforming the pedestrian into the lyrical. His subtle, sculptural interventions and specific installations address the momentum of newness and production. As travellers through galleries, private collections, and museums, artworks gain a constellation of tangentially-related objects: panels, plastic sheeting, foamcore, and crates. Miming this frequently unrecognized accumulation of material, Sibony cuts and paints a board of salvaged plywood with half-moon and eclipse shapes, emphasizing both the artwork’s objectivity and the symbolic order of matter and space.

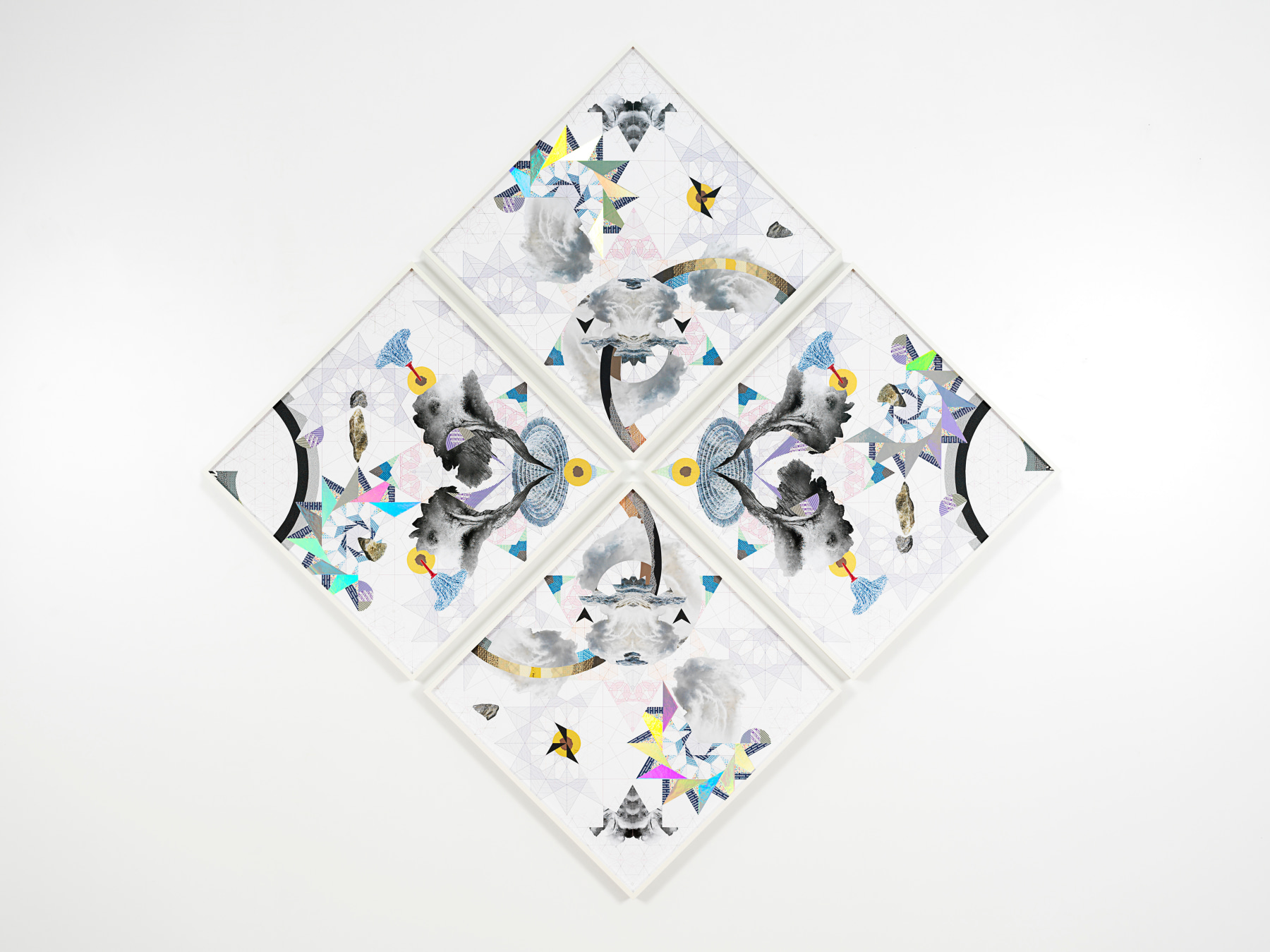

Haegue Yang

Tempestuous Quadruple Attractors – Trustworthy #404, 2020

Various security envelopes, graph paper, sandpaper, laser prints, self-adhesive holographic film on alu-dibond, framed

4 Parts: 22 1/2 x 22 1/2 inches (57.2 x 57.2 cm) each

(HY.334)

Haegue Yang’s “Trustworthy” series (2010–ongoing) consists of framed collages of security envelopes. Here security envelopes, meant to both obscure and reveal information, are stripped of their intended use, arranged, cut, unfolded, and layered in geometric patterns. Like much of Yang’s practice, these works explore the domestic and the traditional in situations in which the familiar becomes all but unrecognizable. In this work, both security envelopes and images of ocean waves become mesmerizing geometric investigations of the tensions between form and content.

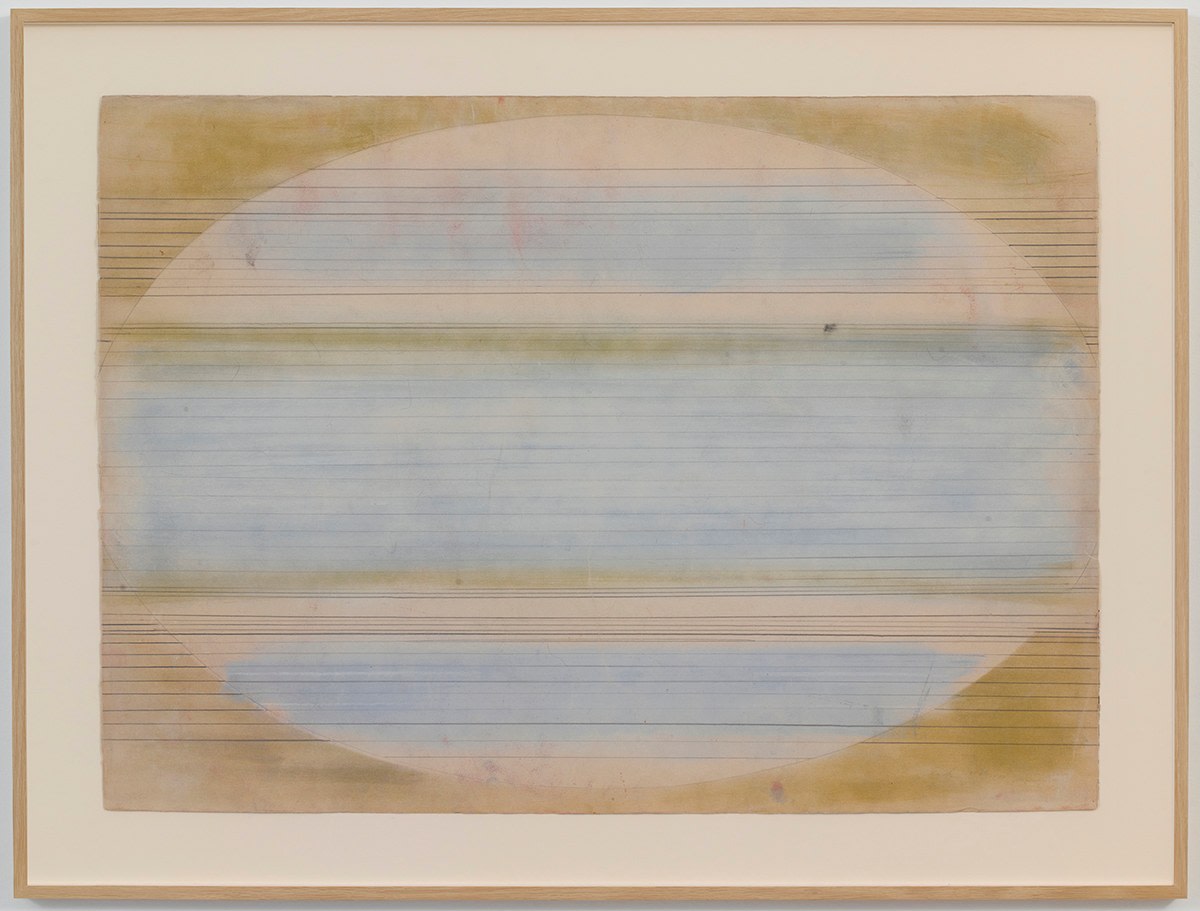

Ed Clark

Untitled, 1972

Mixed media on paper

Paper: 29 5/8 x 41 3/8 inches (75.2 x 105.1 cm)

Frame: 36 7/8 x 48 3/4 x 1 1/2 inches (93.7 x 123.8 x 3.8 cm)

(EC.011)

The canon of Postwar Abstraction has historically underrecognized the contributions of Ed Clark, an experience shared among the generation of Black painters including Jack Whitten and Sam Gilliam. In the 1970s, Clark began a series of experiments with the painterly plane, engaging with stripes and the oval form. Clark’s work partially refutes Abstract Expressionism’s signature spontaneity, relying on meditative regiment. Upon outlining the ellipse, Clark filled these compositions with colored bands, delineated with masking tape. Evidencing an astute sense of color and technique, Clark intuited the ethereal optical effects produced by the mixing of media. In Clark’s view, painting activated the body entirely and transcendentally—he often described physical and spiritual oneness with his works.

Trisha Baga

Frankenstein, 2020

Acrylic on canvas

11 x 14 inches (27.9 x 35.6 cm)

(TB.675)

Trisha Baga is known for her immersive multimedia installations that assemble 3D video, handcrafted objects, and found materials. Further demonstrating the breadth of her practice, Baga’s latest series places her contemporary muses into the traditional genre of still life painting. In Frankenstein, cables and microchips embed themselves into a tablescape of fruits. In the center sits a swirling red prop—repurposed from Baga’s video work entitled 1620 (2020), where it symbolized science. Aligned with Baga’s ongoing exploration of technologically-mediated identity, the painting titles itself after Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking science fiction novel. Like Shelley, Baga comments on the meeting of nature and science, producing new images and narratives out of fragmentary cultural parts.